_______________________

Roy Oldfield Calvert

DFC and Two Bars, midSerial Number: NZ404890

RNZAF Trade: Pilot

Date of Enlistment: 1st of December 1940

Date of Discharge: 15th of March 1945

Rank Achieved: Squadron Leader

Flying Hours: 59 OperationsDate of Birth: 31st of October 1913 , in Cambridge

Personal Details: Roy Calvert was the second son of Mr and Mrs George Calvert, of Victoria Road, Cambridge, who were well known for their department store in the town. Roy was educated at Cambridge Primary School, at Southwell School in Hamilton, and at King's College in Auckland. He showed an early interest in aeronautics. Before joining the RNZAF Roy was a wool grader in the Cambridge district.

Service Details: Roy Calvert was to become not only one of Cambridge's most distinguished airmen of the war, but also of the the most distinguished bomber pilots of the RNZAF.

He volunteered for the RNZAF very early on in the war. However on being accepted for the Air Force, he was made to wait for some time before he could commence training, simply because of the backlog of men going into camp. Unlike many potential trainees who were given menial tasks within the RNZAF (like working on an Aerodrome Defence Unit), this was earlier on in the war and there was little organisation of such holding units. So he was made to stay in Cambridge and was left unemployed. Roy had already left his employment as a wool grader, thinking he would be taken quickly into the Air Force.

Before the war Roy had been saving up for his own farm, but he decided to take the money he'd been saving and spend it on flying lessons, just to feel he was doing something positive for his future career. So he began flying lessons at Rukuhia Aeroclub, Hamilton, on a De Havilland DH60 Gipsy Moth of the Waikato Aeroclub.

However before his training was sufficient for him to acquire his license the aeroclub's aircraft was impressed into RNZAF service. So he decided to go to Wanganui, where their local aeroclub's Gipsy Moth had not yet been impressed, and he managed to complete his training in time before the Government also confiscated that much needed trainer.

Roy was eventually accepted into the RNZAF officially and began training at the Ground Training School, Wereroa, near Levin on the 2nd of December 1940. This introductory course in which military life was introduced to Roy and his fellow course members lasted till the 18th of January 1941.

Although already a novice pilot, Roy then went to No 4 Elementary Flying Training School, RNZAF Station Whenuapai, where he gained experience on the De Havilland DH82 Tiger Moths. He was at the EFTS from the 19th of January till the 27th of February 1941.

At this point it was decided he would be trained on mulit-engined aircraft, so he then moved to the Intermediate Flying Training School at RNZAF Station Ohakea. Here he trained on twin-engined Airspeed Oxfords between the 2nd of March till the 1st of April 1941.

Roy's fiancee May had moved to near Wanganui, where she could be near to Ohakea, and she carried on her own war effort there as an ambulance driver for the local Home Guard. She recalls that she'd often visit Ohakea to see Roy and they'd go to dances in the local halls.

Soon Roy stepped up to the Advanced Flying Training School, also at Ohakea, where more complex flying training was accomplished in the Oxfords. This course commenced on the 2nd of April and ran till the 25th of May 1941. At the completion of this course he received his Wings, meaning he was now a qualified RNZAF pilot. However as any pilot will tell you, being qualified does not mean that you are a good pilot - much more training was to come.

After the advanced course he was given Final Leave, which meant he was to return home for a week (26th of May till the 3rd of June 1941) to sort out his affairs and to say goodbye to friends and family before departing overseas. He travelled with May and his parents to Auckland during the end of this week's leave. His father had always handled Roy's monetary affairs, and Roy asked him for a cash advance. This however was not to take with him to England, but instead to spend on a wedding - he and May were married just before Roy stepped onto the boat. May recalls that as the boat departed she fervently waved a silk scarf she'd been wearing, as the ship slowly faded into the distance. Sometime later she received a letter from Roy asking her to send the scarf - which he said was the last thing he saw as the boat departed, and it was his most enduring memory that May was the last one still there waving, though but a tiny speck from his vantage point. She sent the scarf and Roy was to wear it for luck on every operation he flew. May still has the scarf today.

As it turned out Roy was destined for Liverpool, England, via Canada. Upon arrival in Britain, Roy was sent to No 2 School of Navigation, at RAF Cranage, England, where he trained in navigation on the venerable Avro Anson light bomber. This course began on the 4th of August 1941 and lasted till the 13th of September 41.

The next day it was onto No 25 Operational Training Unit, at RAF Finningley, where again he was flying Ansons. A great deal of night time navigational exercises were carried out to simulate bomber missions over Europe. On the 28th of September he left 25 OTU for a short time to go on a course at No 7 Blind Approach Training Flight, also at Finningley, where techniques were learned on Airspeed Oxfords. On the 5th of October 41 it was back to 25 OTU for further training, and between that date and the 20th of February 1942 Roy gained experience on Ansons, Oxfords, Tiger Moths, and some bigger metal - the Vickers Wellington and the Avro Manchester bombers.

On the 21st of February 1942 Roy went with “E” Flight of 25 OTU to RAF Bircotes in England where he flew Avro Manchesters for three weeks till the 12th of March 1942. He then transferred to “D” Flight, 25 OTU, back at Finningley, where he concentrated his flying on Vickers Wellingtons for a further week till the 20th of March 1942.

There was a short period off course now, perhaps for Easter or some other reason, and then it was back to 25 OTU at Bircotes for two days - the 2nd till the 4th of April 1942 - before returning to Finningley on the 4th to complete his course. flying 25 OTU Manchesters till the 14th of April 42.

On the 14th of April Roy was posted to No 50 Sqn RAF, at RAF Skellingthorpe in England. Just two days later he flew his first operational mission - a night raid on Lille - the first of 59 operational bombing raids that he'd eventually notch up over enemy territory . See the link at the bottom of this page to read more on Roy's bombing operations.

With 50 Sqn Roy continued to fly the dreaded Avro Manchesters, which like most pilots of the type, Roy hated, and he also got some time up on the Airspeed Oxfords. Things looked up soon though when he got his first experience on the mighty Avro Lancaster, which was a four-engined development of the Manchester yet it was a far superior aircraft in every way, especially safety. The Lancaster became Roy's favourite type to fly and he spent a lot of time perfecting his skills in it and developing techniques such as the defensive corkscrew dive that he'd later use in combat to avoid enemy fighter attack. The fighters would always attempt to attack the Lanc's belly, which was the least defended area, but the corkscrew prevented the fighters getting a clear shot (despite much dislike for the manouvre from Roy's crew members, but it did save their lives on several occasions).

On the 21st of June 42, No 50 Sqn moved to RAF Swinderby while the runway at Skellingthorpe was being sealed. Whilst there Roy operated Manchesters and he also gained some flying hours in another heavy bomber, the Handley Page Halifax - though not on an actual mission. By the 16th of October the squadron was back at Skellingthorpe, where Roy remained, operating mainly Lancasters, till the 14th of February 1943.

It was the policy of the Royal Air Force (as with the RNZAF), that after a certain period of operations aircrew would then go onto a 'rest period', where they become instructors and train up new boys using their own experience, whilst also having a mental breather from the horrors of operational flying for at least a few months. So on the 16th of February Roy began a course at No 1660 (Heavy Aircraft) Conversion Unit, at Swinderby, where he flew Lancasters for eight days, till the 23rd. This was probably for him to learn how to convert other pilots to the Lanc, rather than convert himself as he'd already been flying the type for many months.

He was now off-operations and was learning to be an instructor, so he then went onto No 3 Flying Instructors School, at Castle Combe in Wiltshire, England. During the period of 24th of February 1943 till the 28th of March 1943 he flew Airspeed Oxfords here while also learning the skills of training others.

Then on the 29th of March he was back to 1660 Conversion Unit at Swinderby, where he was now a fully qualified instructor on Lancaster Mk I, Lancaster Mk III, Short Stirlings and Halifax bombers till the 12th of January 1944.

He spent a further five days till the 17th of January 1944 at No 5 Lancaster Finishing School, Syerston, England flying Stirling and Lancaster bombers.

At this point after a considerable period as an instructor, Roy went back onto operational flying on Lancasters with No 630 Squadron at RAF East Kirkby in Lincolnshire. (Incidentally East Kirkby is now a museum and still has a taxiable Lancaster as resident). He flew with the squadron till the 24th of August 1944, when he returned to No 5 Lancaster Finishing School, Syerston, England for a month, till the 20th of September 1944.

On the 20th of September Roy was moved to No 12 PDRC, Brighton, England, a personnel distribution centre, where he was assigned a ship home to New Zealand.

Roy returned to Cambridge following the war where he continued farming. He passed away in 2002 after a fight with emphysema.

Roy was one of only four New Zealand airmen to receive two bars to his Distinguished Flying Cross. This means he won the DFC three times. The three other New Zealand airmen to be awarded the DFC and Two Bars were Sqn Ldr Colin Falkland Gray, RAF (the highest scoring New Zealand fighter pilot ever); Sqn Ldr Alfred William Gordon Cochrane, who flew with No 126 Sqn; and Sqn Ldr Keith Frederick Thiele, who was CO of No 3 Sqn and later with No 467 Sqn RAAF.

When Roy was awarded his first DFC, the Waikato Independent newspaper reported that he was “a most popular young Cambridge man”, and it continued by adding;

“Roy Calvert is the type to make a good airman. A clean-living lad, after leaving school, he learned to look after himself on big sheep stations in the North Island. He was keen on athletics, and was successful at King's College, where on one occasion, he won the school's annual steeplechase. At Southwell School he put up a high jump record that has not since been eclipsed at this school. Boxing and golf also had his active interest. Cambridge folk will continue to watch the record of Flying Officer Roy Oldfield Calvert, DFC, and we join with them all in offering congratulations to the parents.”

Decorations

Roy was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross on the 20th of October 1942 for his part in several combat missions over hostile territory whilst flying Avro Manchesters and Lancasters with No 50 Sqn RAF. Also recognised on the same citation was Roy's navigator, Pilot Officer Sears. The DFC citation read:

“Flying Officer Calvert and Pilot Officer Sears as pilot and navigator of aircraft respectively have flown together on many sorties. Whatever the weather or the opposition they have always endeavoured to press home their attacks and, on numerous occasions, have obtained excellent photographs. Throughout their tour of duty, these officers have displayed a high standard of skill, together with great devotion to duty. ”

The investiture for this medal saw Roy going along to Buckingham Palace, where he received it personally from HM King George VI.

A few days later he was wounded on another mission. By November 1942 he'd been discharged from hospital and was back flying Lancasters with No 50 Sqn again. On the 15th of December 1942 he received a Bar to his DFC. The citation, which also recognises navigator Flight Sergeant Medani to this Bar read:

“As pilot and navigator of aircraft respectively, Flying Officer Calvert and Flight Sergeant Medani have participated in numerous sorties, including attacks on heavily defended areas in western Germany, and daylight raids on Le Creusot and Milan. During a recent sortie, Flying Officer Calvert's aircraft was subjected to heavy anti-aircraft fire, sustaining much damage. The wireless operator was killed, and both the pilot and navigator were wounded. The aircraft became difficult to control, but Flying Officer Calvert, although he had a piece of shell splinter in his left arm, set course for home. Sergeant Medani, despite the severity of his wounds and subsequent loss of blood, continued his duties until he collapsed. Even so, he succeeded in giving his pilot a final course which enabled him to reach an airfield in this country where he made a skilful crash landing in bad visibility. Both these members of aircraft crew displayed great courage and tenacity in the face of harassing circumstances.”

On the 15th of October 1943, while now a flying instructor with No 1660 HCU, RAF on Lancasters, Roy received the following Flying Log Book – Green Endorsement”

“On a dual instruction flight the port tyre of Flight Lieutenant Calvert's aircraft burst when pupil was about to make a landing. Flight Lieutenant Calvert took over control of the aircraft and through outstanding pilotage landed the aircraft safely causing no additional damage.”

On the 8th of June 1944 Roy was given a Citation Mention In Despatches, which simply read:

“In recognition of distinguished service and devotion to duty.”

By August 1944 he had been promoted to Acting-Squadron Leader and he was awarded a Second Bar to his DFC on the 15th of September 1944 for his service while flying with No 630 Sqn RAF, again on Avro Lancaster bombers. That long citation read as follows:

“Since joining this Squadron in January 1944, Acting Squadron Leader Calvert has taken part in attacks against many strongly defended targets in Germany, including Berlin and Leipzig. He has consistently shown skill, determination and reliability, and as captain of his aircraft he has set a high standard to the other members of his Squadron. His operational experience and enthusiasm have been invaluable in the training of new crews.”

Roy was interviewed in 1993 by Colin Hanson for his book By Such Deeds, in which he records:

"In Feb 1993, Sqn Ldr Calvert recalled that one of the ‘highlights' of his operational flying occurred on 30 May 1942. He set off from RAF Skellingthorpe, the base for 50 Sqn, in Manchester L7525, on his fourth sortie – for Cologne on the first 1000 bomber raid. In his words – “The trip was uneventful until approaching the target – we could see the target lit up by flares and blazing well. The Rhine stood out clearly in the moonlight and we made our run-in at 9,000' from the north-east to south-west. We could see our aiming point which was close to the cathedral and F/S Taerum, my Canadian navigator (later to go with Guy Gibson on the Dams raid), guided me through. Just after he said ‘bombs gone' we were hit by flak and the starboard motor burst into flames. I closed the bomb doors, pressed the fire extinguisher and feathered the airscrew. As the motor stopped the fire went out so I dived to try and clear the target area as quickly as possible. We came out of the searchlights about 7000' to the south of the city and F/S Taerum gave me a course for home. I found that the aircraft would not maintain height on one engine so I decided to try the dud engine to see if I could get a little help from it. However on unfeathering the prop the engine burst into flames again so I re-extinguished and re-feathered and fortunately the fire went out a second time.

I then asked the crew to stand by with parachutes on or handy and be ready to abandon the aircraft. We were still gradually losing height so I asked them to throw anything movable overboard to make us a little lighter. By this time we were down to 1500' but the good engine was running well and I didn't want to risk giving it more revs at this stage. At 1000' I decided that if the coast came up shortly we would have a show of at least making it far out on the Channel. We crossed the coast at 200' and headed for home – no sign of fighters and we entered a filmy sheet of cloud – then we threw our guns and ammunition overboard. At 100' I closed the radiator flaps which gave us another 5mph, and using maximum revs, found that I could climb up to 200' until overheating forced me to open the flaps and reduce revs. We gradually came down to 100' again so I kept on repeating this process until we saw the English coast ahead.

The aircraft was getting lighter in fuel and easier to manage as we crossed the Thames Estuary and overland we received more lift and could gradually climb to 800' without overheating the engine. We dropped down at Tempsford aerodrome, pleased to feel earth beneath our feet once more. On inspection we found a piece of shrapnel had burst the pipe carrying coolant around the engine and that had been the cause of the fire. The Manchester had two Rolls Royce Vulture engines which were designed to produce 1400hp but they were rushed into production without adequate testing – they were short on power and had a name for overheating and being prone to catch fire.”

Details of Death: Roy died on the 26th of March 2002, aged 88, after a battle with cancer. He was buried at the RSA Cemetery at Hautapu, Cambridge

Connection with Cambridge: Roy was born in Cambridge, New Zealand and lived in the town and district for all his life pre and postwarThanks to: The late May Calvert for her valued assistance, and to Colin Hanson for allowing the above passage to be used on this website.

In His Own Words

A few years before his death, Roy wrote down a few of his memories for his grandson who was doing a school project. This was written by Roy with the aim that children could understand it, but it gives an interesting insight, straight from the man himself. This essay was kindly supplied by May Calvert.

What Was It Like To Be A Bomber Pilot In World War II?

By Roy CalvertFirstly I must stress the importance of training - no one is of much use until they are thoroughly qualified for the job they are asked to do - and that applies to every occupation. Even in war time, in Bomber Command, pilots were not asked to go into action against the Enemy until they not only could fly their aircraft safely and well but also knew how to cope in case of emergency such as engine failure, fire or other damage to the plane.

In my case it took 18 months from the time I joined the Air Force to the time I was posted to an Operational Squadron in England. I was six months in N.Z. doing elementary flying training on Tiger Moths and Airspeed Oxfords - the rest of the time in England doing Navigational training and learning to fly Wellington and Manchester aircraft. We did a lot of cross-country flying all over England, Scotland and Wales by night. There being a total black-out of course, except for flashing beacons usually near aerodromes which flashed a Morse code signal for which we had charts, giving us our position.

In daylight of course it was no great problem; the maps were so good. They had almost every detail marked on them - all roads, raliway, even small patches of bush and anything else of note. Some aircrew from Canada, America or Australia found it difficult for a while as they had been used to wide open spaces and towns with their lights on which you could see miles away.

Our navigation in 1942 was quite primitive by today's standards - it was called D.R. (Dead Reckoning). You flew on a certain course which had been adjusted for compass error and a given wind velocity and direction - then as you received a "Fix" of your position you were able to get a new wind direction and so fly an adjusted course in order to get to your objective. As time went on and we received better navigational aids (Radar) we could even bomb through 10/10 cloud (total cloud cover) until Germany found a counter to it. If the sky was reasonably clear it was quite easy to pick out rivers - even from a great height - especially if there was some moon showing.

Before every operational flight we would first of all have a short flight to test our plane to make sure everything was working satisfactorily - the engines to make sure you had maximum revolutions for take-off; and the hydraulics O.K. for rotating the gun turrets, etc.

We would then have a meal, probably bacon or sausages and eggs, and go to a briefing for the whole crew. We would be told the target for the night - and the reason for it. It might be an arms factory; an industrial centre; railway junction; flying bomb site; shipping; laying mines at low level - anywhere throughout Europe. We would be told where all the heavily defended places were on our route, especially close to the target and the weather expected over target and when we got back to base.

My first two Operational trips on 50 Squadron were taken with experienced pilots to give me confidence over enemy territory I suppose, but they were easy ones as things turned out. We were flying Manchesters, which were really twin-engined Lancasters - the "Vulture" engines had not been sufficiently tested and did not produce the power they were designed to do. Also they had a reputation of being liable to catch on fire. My third trip was my first as Captain of aircraft. We went to "Le Mans" in France dropping leaflets -which was quite common at that stage of the war - mainly to inform the French people what was going on in the world outside and to combat German propaganda.

A heavy bomber crew consisted of seven members: Pilot, Navigator, Flight Engineer, Bomb Aimer, Wireless Operator, Mid-Upper Gunner and Rear Gunner.

My fourth trip was a different proposition - it was the first 1,000 bomber attack on Cologne on May 30th, 1942, and we were loaded with incendiaries. There was no mistaking our target as we made our run in to bomb at 9,000 ft. The city was ringed with searchlights and stood out clearly on a bend of the river Rhine, and was well alight as we dropped our load. The next moment our starboard engine burst into flames. In a slight dive to clear the area quickly I pressed the fire extinguisher button for that engine and fortunately the fire went out.

I then feathered the airscrew which turned the blades edge on to the slipstream thereby reducing drag. I found I could not maintain my height with the port engine doing as many revs. as I dared let it do - we had a long way to go. I decided to try the starboard engine again - to see if I could get a little help from it - but it immediately burst into flames again. So I shut it down again and refeathred the airscrew.

Then I told the crew to put their parachutes on ready to abandon the aircraft if necessary and to throw anything movable overboard. We gradually lost height and crossed the coast about 200 ft up, determined to get back to England. We then entered low filmy cloud so I asked the gunners to get rid of their guns and ammunition. We were now down to 100 ft. I closed the radiator flaps - giving us extra speed and climbed up to 200 ft. The engine overheated so i opened the flaps and the engine cooled down as we gradually came down to 100 ft again.

I kept repeating that process all the way the Channel until we arrived in the Thames Estuary. We were getting lighter in fuel and on arriving over land once more received extra lift and I found I could even climb without the engine overheating. We dropped down at Tempsford aerodrome and an inspection showed a piece of shrapnel had burst the coolant pipe and Glycol, which has alcohol in it, in contact with a hot engine had been the cause of our fire.

Incidentally my Navigator on the trip was Terry Taerum, a Canadian who later flew with Guy Gibson on the Dams raids.

Shortly after this trip we converted onto the four-engined Lancaster with Rolls Royce Merlin engines. A relaible and beautiful aircraft to fly.

The foregoing will give you some idea of the life of a Bomber Pilot. Operational trips were unpredictable - you could strike trouble on your first trip just as easily as your last one. Bomber Command decided that 30 trips consisted a tour of operations, then crews were stood down for a rest and were then posted to a training squadron to pass on their experience to new crews. Quite a number of pilots decided after some months of instructing that it was almost as dangerous as being on operations and applied to go back on operations again. A second tour was supposed to be for about 20 trips. I was fortunate enough to do 33 trips on my first tour and 26 on my second. So you see I was very lucky to survive as we ranged over the whole of Europe bombing targets in Germany, Italy and France.

My first tour of ops was in 1942 and it was fairly free and easy in those days. Owing to the smaller number of aircraft involved we were able to choose our own height and direction over the target and the route over and back was not critical as long as you stayed clear of heavily defended areas. In 1944 on my second tour conditions had changed dramatically - the numbers of aircraft involved had quadrupled. The danger of collision was high so every squadron was given a height (within 300 ft) a certain time (within 3 mins.) ove rthe target, and a definite course to fly on. The variation in height for 500 to 800 a/c would be about 17,000 to 21,000 ft, and would apply to targets such as Hamburg or Berlin, etc.

I have just had a request from a Historian for further information so I must get on with it. I hope this will serve your purpose and i appreciate your interest in the subject.

________________________________________________________________

)

PHOTOS: After The First Daylight RaidBelow is a photo from Roy Calvert's collection depicting five aircraft Captains from the first daylight raid his squadron went on. The men are identified on the rear side as: Jack Abercromby (Scottish, standing left), Sqn Ldr Moore (Australia, standing centre), Sqn Ldr Hugh Everitt (English, standing right), Drew Wyness (English, kneeling left) and Roy Calvert (New Zealander, kneeling right). Drew Wyness went on to serve with No. 617 (Dambusters) Squadron, after the famous Dams Raid, and was sadly killed. Photo via May Calvert

Operation Post Cards

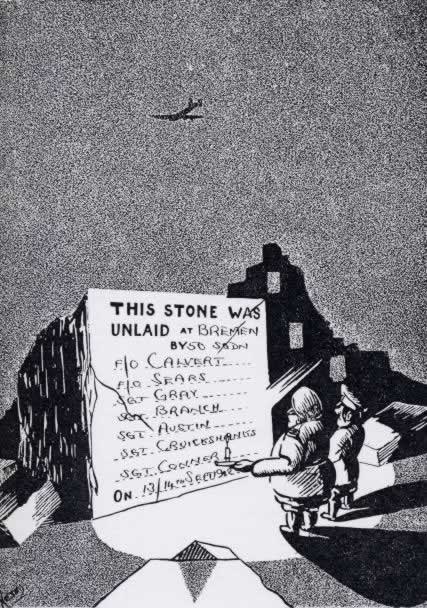

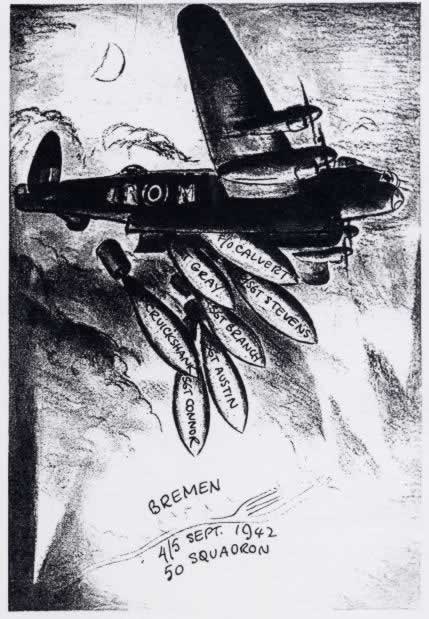

Roy Calvert 's No 50 Squadron Commander had a little thing going where any crew that had received damage to their aircraft during a raid would receive a token souvenir. This took the form of a post card sized cartoon, with details of the raid on it. It seems that Roy received at least eight of these cards, in two different designs. Two of them are shown below.

Above: A card received following a raid on Bremen on the night of 13th and 14th of September 1942 that depicts Hitler and Goering inspecting the damage they'd made.

Another card design depicting a 50 Squadron Lancaster dropping bombs, this time on Bremen on the night of the 4th and 5th of September 1942.

The Downing of Taipo

From Roy's 6th operation through to his 31st, flying with No 50 Squadron RAF, he and his crew flew a regular aircraft, Avro Lancaster R5702 "S". Roy had dubbed this faithful Lanc with the nickname and noseart of Taipo, which is the Maori word for devil. This aircraft was very special to Roy and his crew, because it got them through a great deal of trouble unscathed, until that 31st op on the night of the 9th of November 1942. On this fateful raid Taipo was attacked by flak and fighters, and for the first and only time in his RAF career Roy sadly lost a member of his crew. However he bravely managed to guide Taipo back to Britain, crash landing her at the RAF Station at Bradwell Bay Roy was awarded his second DFC for this action.

Above: This snap shows R5702 VN-S "Taipo" sometime before the raid on the 9th of November 1942. The caption written on the rear side by Roy reads "R5702 The Old Faithful, Skellingthorpe, 1942". Roy Calvert via May Calvert

Above: Taipo after the fateful raid, peppered with flak holes and now minus its spinners and propellers, and sitting on its belly - the way it landed at Bradwell Bay as the undercarriage was damaged. This is pieced together from three separate photos which explains the slight tone variation. I believe these photos were taken by an official RAF photographer but this is unconfirmed. Via May Calvert

Above: Taipo's cockpit, showing the damage inflicted by flak that had injured pilot Roy Calvert. Via May Calvert

Above: The uninjured members of the crew of Avro Lancaster R5702 "S" 'Taipo' following the raid on the night of the 9th of November 1942, sit in one of the holes put through the wing by enemy action. Left to right are Pilot Officer Power (American, 2nd Pilot), Sergeant Cruickshank (English, Rear Gunner), Sergeant Wilson (Air Bomber) and Sergeant Alan Connor (Australian, Wireless Operator/Air Gunner).

Roy Calvert DFC** mid's Operations

Lastly we present the operations that Roy and his crews made during WWII, copied with kind permission of May Calvert from Roy's Flying Logbook. The operations are split over his two tours, the first with No. 50 Squadron RAF, and the second with No. 630 Squadron RAF. Please click the links below to view these extra pages:

| Home | Airmen | Roll of Honour |

|---|